Media & Press

‘Survival’ takes a ‘painful’ look at research failure

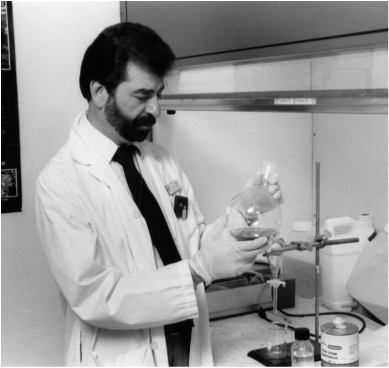

BY JASON WINDERS OCTOBER 6, 2016 In his book, ‘Survival: A Medical Memoir,’ Lorne Brandes, MD’68, pictured here in his University of Manitoba lab in the 1980s, chronicles his decade-long journey toward an, ultimately, failed attempt to develop a revolutionary cancer drug. Lorne Brandes, MD’68, doesn’t mind sharing the ugly stuff. “It had to be that way. I was trying to chronicle in the most honest – some might say most painful – way possible as to how things did or did not develop for me,” said the recently retired University of Manitoba oncologist. “I guess there are scientists out there who have nothing but success in their entire careers. I can only tell you how it was for me.” In his book, Survival: A Medical Memoir, Brandes chronicles his decade-long journey toward an, ultimately, failed attempt to develop a revolutionary cancer drug. He admits his is not a unique story – as most science ends in failure – but it is a story rarely told. Ego often gets in the way of tales like these, Brandes said. “But not everyone is a Watson and Crick,” Brandes laughed. During the 1980s, Brandes was researching the breast cancer drug tamoxifen and looking for a substance to bind to ‘antiestrogen binding sites’ within cells. To that end, he synthesized an antihistamine called DPPE (also known as tesmilifene), which appeared to curb unwanted uterine growth, prevent tumour formation and increase chemotherapy drugs’ effectiveness. What followed this discovery were years of fizzled funding, short-circuited trials, bureaucratic frustration, renewed hope and, ultimately, disappointment. Survival: A Medical Memoir is a ‘warts-and-all’ look at what goes on inside the lab, around the conference table and behind closed doors of medical research. “This is a story that ends in failure. As I was writing this, I kept saying, ‘Who is going to be interested in reading a book about a drug that failed?’” he said. “Fortunately, people smarter than I pushed it forward. They said people will want to read it; they will want to read it because it is a cautionary, true tale about what I had experienced. “In some ways, it doesn’t matter how the story turned out. It is the journey along the way that makes it worth telling.” Although his book ends in failure, Brandes’ career has been a long and successful one. Upon graduating from the University of Windsor, he opted for Western above three other medical schools in the province. On campus, he met and married his wife Jill Colman, BA’66, Ed’67. Following his internship and first year of residency at Western, Brandes spent 1970-71 with chemotherapy pioneers, Drs. David Galton and Eve Wiltshaw, at the Royal Marsden Hospital (London, United Kingdom). He completed his training in hematology/oncology at the University of Manitoba under Dr. Lyonel Israels, one of Canada’s foremost hematologists and medical researchers. Brandes joined the Faculty of Medicine at Manitoba in 1975, where he became a tenured professor in the Department of Medicine and the Section of Hematology/Oncology at CancerCare Manitoba. In addition to his oncology practice, he has conducted laboratory research – including the powerful story chronicled in Survival: A Medical Memoir. He retired in September, 2015. Brandes started writing the book early on in his research, perhaps with an eye toward providing a record of his discovery. But once it became clear there would be no happy ending, he shelved the project. “I regarded myself at that point – perhaps rightly or wrongly – as a failed scientist. That was it for the book,” he said. For eight years, the book sat as a lone Word document on his laptop. “I didn’t even back it up. Would you believe that?” When he semi-retired a few years ago, his wife talked him into revisiting the manuscript. “I spent three or four nights reading it again. As I did so, I thought, ‘Geez, this is an interesting story, this is a good story.’ Enough time had passed, enough people had said the book needed to be finished that I decided it was time,” he said. “And I quickly backed it up at that point, by the way.” Now out of the lab, Brandes discovered a far more venomous arena – book publishing. Efforts to convince university and popular presses to publish the book ran into a series of roadblocks – his memoir was too niche, perhaps too scientific for a broad audience. “If you are a John Grisham or J.K. Rowling, you are taken care of. I knew I was not that,” he laughed. “I knew I had a niche book – a book I would really like people to read and learn something from. I have always been a teacher at heart.” He ended up self-publishing the book through FriesenPress. With his book released earlier this year, Brandes has been hustling to promote it – landing it in all major online retailers, as well as targeting university book stores and libraries across North America. In just six months – phone call by phone call, email by email – he has placed the book within 60 universities and, just last week, the New York Public Library collection. “I published the book; I am going to promote the book,” he said. “But I figure, any guy who did what I did all those years isn’t going to be put off by trying to promote a book by himself.” __________________________________________________________

Dr. Lorne Brandes ’64 at the time of his anticancer drug discovery University of Windsor ALUMNI PROFILE BY JENNIFER AMMOSCATO September, 2016 THE FIGHT TO FUND A CANCER KILLER Dr. Lorne Brandes ’64 According to Forbes, a pharmaceutical company can expect to spend $350 million on a new drug before it is even for sale. Add to this the fact that up to 95 per cent of experimental medicines studied each year fail to be both safe and effective in human trials, and it underscores the monumental effort it takes to successfully launch a new drug. University of Windsor graduate Dr. Lorne Brandes BSc ’64 knows firsthand this challenge. In 1999, the pharmaceutical company that had funded the breast cancer trial for an anticancer drug he’d discovered stopped it cold because of what it perceived as ineffectiveness. Brandes’ new book, Survival: A Medical Memoir (From Drug Discovery To Clinical Cancer Trials), tells the story of his 23-year odyssey to see his discovery put into the hands of those he hoped to help. Now retired, he has chronicled the development of the novel antihistamine drug, DPPE, which helped chemotherapy drugs cure laboratory mice of cancer while protecting the bone marrow. Brandes, MD, FRCPC was a professor of medicine at the University of Manitoba when he sought to take DPPE from the laboratory into human testing. “I researched the drug and then took it through the regulatory hoops and into early human clinical trials during a span of 12 years,” says the alumnus. He started in 1984 and handed it over to Bristol- Myers Squibb in 1996. The pharmaceutical company declined to invest any further, however, after it decided that preliminary results of a major breast cancer trial didn’t warrant it. Brandes’ disappointment turned to elation 18 months later, when the stunning discovery was made that women who had received DPPE plus chemotherapy survived 50 per cent longer than women who received chemotherapy alone. “I and everyone else were dumbfounded. It was totally unexpected.” Brandes says. “While it is not uncommon for drugs to be pulled if the expectations of drug companies are not met, many people felt that, in the case of DPPE, Bristol-Myers had acted prematurely,” he adds. A year later, a small Canadian biotech company, YM BioSciences Inc. of Mississauga, rescued the drug. With a combination of luck, venture capital and the FDA’s blessing, it took DPPE back into a final trial needed for its approval. Brandes’ book is more than a scientific recounting. It is a unique and very personal story, full of twists and turns, with an international cast of characters in the world of cancer research, medical oncology, the pharmaceutical industry, and regulatory agencies (Health Canada and the FDA). Dr. Agnes Klein, Health Canada’s director of the Centre for Evaluation of Radiopharmaceuticals and Biotherapeutics, was actively involved in approving DPPE for the first human trials. In the book’s foreword, she wrote, “To say that I saw (Brandes), from the start, as a ‘unique character’ is an understatement. He was passionate and persistent about his findings on DPPE, his basic and clinical research, as well as his practice of oncology.” She calls the book a reminder to “researchers, physicians, other health care professionals, and even a regulator like me, that the road to a successful drug is paved with pitfalls, despite all good intentions, and that, while many active substances never ‘make it’, much new knowledge can be acquired along the way.” A 2012 article in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery says the number of drugs invented per billion dollars of R&D invested has been cut in half every nine years for half a century. Brandes’ book has touched off the discussion once again. Some of the findings reported in it were, at the time, widely covered in the press, including the Winnipeg Free Press, The Globe and Mail, CBC, CTV, Macleans, U.S. News and World Report, The Wall Street Journal and CNN. One of the book’s key messages is that a single investigator at a single institution taking a drug from the laboratory bench into human clinical trials without support from a drug company or clinical trials group was both unique and a product of 1990s culture. Says Brandes: “I do not believe it could happen in 2016 because the ever-increasing layers of institutional bureaucracy and risk-averse lawyers that permeate modern-day society would likely prevent any similar discovery from getting off the ground. “It’s a sad reality.” Survival: A Medical Memoir (From Drug Discovery To Clinical Cancer Trials) is available in the Campus Bookstore, or may be ordered from FriesenPress, Chapters/Indigo, Amazon, Kobo and iTunes _____________________________________________________________________ |

|

www.statnews.com

How I Took A Drug To Clinical Trials On My Own 30 Years Ago. That Couldn't Happen Today

By Lorne Brandes

Developing a new drug and ushering it through rounds of clinical trials usually takes a huge team of scientists and billions of dollars. I did it without the support of a drug company or a clinical trials group and for a fraction of the cost. My 23-year odyssey offers an intimate and detailed look into how that happened while offering lessons that may give today’s innovators and bureaucrats pause for reflection. As a cancer specialist who likes to understand how things work, I was always on the lookout for new compounds that could fight cancer. In the early 1980s, my lab at the Manitoba Institute of Cell Biology at the University of Manitoba was conducting research on tamoxifen, a drug used to shrink estrogen-driven breast cancer. It works by preventing estrogen from latching onto a specific cell receptor so the hormone can no longer fuel the growth of breast cancer cells.

A new discovery that tamoxifen also homes in on another “anti-estrogen binding site” intrigued me. Wondering if blocking it could help tamoxifen shrink breast cancer, I started looking for compounds that could do just that.

As I describe in “Survival: A Medical Memoir,” my chronicle of the discovery and testing of DPPE, my colleague Asher Begleiter and I started with some off-the-shelf reagents to create tamoxifen-like molecules using standard organic chemistry techniques. On our second try, we created a creamy white powder that lacked one of tamoxifen’s three chemical rings. It didn’t prevent estrogen from binding to its receptor (which was good) but was as powerful as tamoxifen in its ability to latch onto this new antiestrogen binding site.

We called the compound DPPE, an acronym for its long chemical name. It later came to be known as tesmilifene. We turned it loose on a cell culture of estrogen-driven breast cancer cells. The results were unequivocal — DPPE slowed the growth of these cells; higher doses killed them, just as tamoxifen did.

DPPE patents were quickly filed and animal studies approved within one or two weeks. The human protocols required by the university ethics committee and health regulators got the go-ahead within 50 days. The entire regulatory process took just eight months from start to finish.

Although DPPE was an experimental treatment, the government of Manitoba took the unprecedented step of funding the early patient trials at a time of widespread budget austerity.

Those initial Phase 1 and Phase 2 studies first combined DPPE with other chemotherapy agents among individuals with late-stage cancers of various types, then concentrated on patients with metastatic breast and prostate cancer. The results showed such promise that they were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

After 12 years of going it alone, we licensed DPPE to Bristol-Myers Squibb in 1996. Despite early success in a Phase 2 trial in advanced breast cancer, a follow-up Phase 3 study showed that DPPE didn’t appear to add any additional benefit to the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin against breast cancer. Bristol-Myers Squibb stopped the trial before it was scheduled to end and abandoned DPPE before we could measure its effect on survival, a prespecified outcome.

That was unfortunate, because 18 months later we learned that women who received DPPE plus doxorubicin lived 50 percent longer than women who received doxorubicin alone. Even so, Bristol-Myers Squibb didn’t want the drug back.

A Canadian company, YM BioSciences, retested DPPE in a US Food and Drug Administration-approved Phase 3 trial in more than 700 women with advanced aggressive breast cancer. That study, completed in 2007, showed no survival benefit among the women receiving DPPE. As is all too common with negative studies, the results of that trial were never published.

Could this happen today?

I don’t believe I could have developed DPPE today. The nurturing culture that propelled it forward in the 1980s and 1990s stands in stark contrast to the ever-increasing layers of institutional bureaucracy and risk-averse lawyers that now permeate biomedical research.

I often wonder how the pioneers in chemotherapy, whose breakthrough treatments have saved countless lives, would have fared had they been working within today’s research framework. It’s unlikely that Sidney Farber, regarded as the father of modern chemotherapy, would have been able to proceed as quickly as he did in 1948 — after discovering that folic acid stimulated the progression of leukemia — to administer the folic acid antagonist methotrexate to children with leukemia.

In 1965, Emil Frei and Emil Freireich got a quick green light to treat children with leukemia using a previously untested combination of four chemotherapy drugs, dubbed VAMP. In his highly acclaimed book “The Death of Cancer,” Vincent DeVita writes, “When changes [to VAMP] were agreed upon, they were put into practice the next day. Some aspect of VAMP — dosage or the interval of treatment, say — changed from week to week, all in an attempt to make it more effective.” Try doing that with the National Cancer Institute or FDA in 2016!

The relative lack of institutional and regulatory red tape during that golden period propelled innovation in ways that aren’t possible today. At the same time, lives were unnecessarily lost in the haste to offer new hope to patients because the “rules of the road” in cancer chemotherapy were still rudimentary. As time passed and lessons were learned, treatment protocols became ever more strict, to the point that bureaucracy now prevails in full force.

Has bureaucracy gone too far?

There is no question that oversight is essential to ensure high standards and patient safety. Yet today’s bureaucratic and legal maze has increased to such a degree that it is stifling innovation. Researchers and physicians commonly complain that inordinate paperwork, coupled with long delays in approval of laboratory and clinical protocols, severely hamper their progress.

Unless this changes, I fear that many of our best and brightest academics will depart our universities for the private sector, or leave science altogether. Yet, that need not happen. “Survival’s” story provides us with a lesson from the past, and it is this: If we can ratchet down bureaucracy to the still-workable and effective level that allowed me to develop DPPE thirty years ago, everyone will benefit.

Lorne J. Brandes, MD was senior oncologist at CancerCare Manitoba and professor of medicine at the University of Manitoba until his retirement in 2015. He is the author of “Survival: A Medical Memoir” (FriesenPress, 2016).

___________________________________________________________________________________

The Jewish Post & News

New book by Winnipeg oncologist Lorne Brandes tells fascinating tale

"Survival: A Medical Memoir", by Dr. Lorne Brandes

By BERNIE BELLAN

In his over 40-year career as a leading oncologist based in Winnipeg, Lorne Brandes developed a reputation not only as a caring doctor for thousands of patients, he was also a brilliant researcher and an acclaimed teacher at the University of Manitoba medical faculty. Now he has just published a memoir chronicling his years in cancer research during which he took a drug discovery from the laboratory into cancer patients.

In describing Dr. Brandes’s career, his publisher’s website states: “Over the years, he treated most types of cancer, but subsequently limited his practice to breast and prostate cancer. Until his retirement in September, 2015, he greatly enjoyed teaching the art and science of oncology to the many students and post-graduate physicians who rotated through his clinics.”

Now, after having retired from practice last fall, Dr. Brandes’ memoir is receiving wide acclaim, both for the scholarly manner in which he details the over 20-year portion of his career that was devoted to testing a drug known as DPPE, and for the human element he injects into telling that story.

I must admit that reading “Survival: A Medical Memoir” was not always easy for me, as there is quite a bit of science involved in the story of how the cancer-fighting antihistamine drug, DPPE, was first discovered and subsequently taken through the myriad of steps necessary to bring any new drug to market. In telling the story of how he first came to realize the potential benefits of DPPE, Dr. Brandes not only delves into the science behind the drug, he explores the very human side of the process of attempting to take it from the laboratory to the pharmacy.

The book was first brought to my attention by Abe Anhang, who suggested it as something we might want to review in The Jewish Post & News. Abe wrote: “Truth be told, this is a book that was written on two levels – one for the researchers and doctors who will read this book to confirm how difficult it is to shepherd a drug through the approval stages, and one for the layperson more interested in the human drama and the challenge that researchers face in the search for drugs that counter disease!

“The book emphasizes all the personal relationships one has to rely on; the dependence on the whims and judgement calls of government regulators who go by the book; and drug company executives who are primarily interested in bringing to market a product as quickly as possible, that can be sold at a profit. All are constantly on the lookout for the miracle drug, and with DPPE, it looked like they had one until the very late stage of the human clinical trials!

“This book is witness to a span of 20 years of effort! One has to marvel at the attention to detail Dr. Brandes had to recall, and then write it down in readable English! One might argue that its greatest strength (its detail) would appeal mostly to other researchers encountering similar problems. While too much detail may be seen as weakness by readers who are only interested in the drama, one can omit that detail and still understand the point that Dr. Brandes is making!

“As one reads this book the question that cries out for response is: if a professional researcher with an impeccable international reputation and training cannot make it happen, how does a drug ever make it through the process, and was this story just one of many, or was it illustrative of many? If one of many, how does ANY drug ever make it through to public distribution? Is it possible that a miracle cancer drug has already been discovered, but for some administrative reason (either at the research level, the government regulatory level or the drug company level) has faltered due to failure in the process, (in other words, human frailty at work)?”

In her Foreword to the book, Dr. Agnes Klein, Health Canada’s Director of the Centre for Evaluation of Radiopharmaceuticals and Biotherapeutics, and someone who was actively involved in approving DPPE for the first human trials, writes about Dr. Brandes: “To say that I saw him, from the start, as a ‘unique character’ is an understatement. He was passionate and persistent about his findings on DPPE, his basic and clinical research, as well as his practice of oncology. This passion likely came from his calling, but also from the Jewish dictum: ‘Tikun Olam’ (saving the world)…The story that he writes is a good read after all the years that have passed. It is a story that was worthwhile writing to have researchers understand that many endeavours do not end successfully. This is true, especially, in the realm of drug development…. I believe the book deserves to be published to remind researchers, physicians, other health care professionals and even a regulator like me, that the road to a successful drug is paved with pitfalls, despite all good intentions, and that while many active substances never ‘make it’, much new knowledge can be acquired along the way.”

What I think readers - even readers for whom the science in the book may be intimidating (count me among those individuals) – will find especially interesting is the fascinating description of how Dr. Brandes worked with a host of other brilliant researchers, many of whose names will no doubt be familiar to Winnipeggers. From Lyonel Israels to Brent Schacter to Frank LaBella – the list goes on and on – describing in full detail how scientific research is brought to fruition. In addition, there is a dizzying array of other characters who appear throughout the book, from other scientists to pharmaceutical company executives, drug regulators and even medical reporters.

Sadly, he also recounts the names of several individuals with whom he worked who have passed on. As a matter of fact, in reading this book, one can’t help but note the irony of how many other brilliant doctors and researchers who made their life’s work a search for better ways to combat cancer, themselves succumbed to this disease.

One other aspect that Jewish readers, especially, may find endearing in “Survivor: A Medical Memoir”, is Dr. Brandes’s self-deprecating wit and, I think it would be fair to say, his awareness of how much his being Jewish played a role in his career. In one chapter in particular, he describes how, prior to a very important meeting with drug company executives, he was warned to tone down his penchant for speaking his mind. His reply, that he would “think Yiddish but act British”, is as apt a description of the quandary that many Jews have faced, not only in academe, but in business as well.

The final takeaway that I’m sure anyone reading this book will be left with is an unmitigated admiration for scientific researchers who, while they may be recognized for their efforts by their peers, plumb away in laboratories for years, constantly worrying about applying for grants, about having papers accepted for publication, and of having their work undermined for no fair reason. While, to a certain extent, drug companies in this book come off looking as nothing more than avaricious opportunists willing to capitalize on years of research conducted in universities and funded by various levels of government – either directly or though government funded agencies such as CancerCare Manitoba – it is doctors and scientists such as Lorne Brandes and his colleagues who often provide the original research that paves the way for huge drug companies to bring miracle drugs to market. To have the patience to persist in the kind of agonizingly complex research that may come tantalizingly close to being translated into a “billion dollar drug”, as DPPE was once touted, yet ultimately to have that research come to naught – well, that requires a special kind of inner discipline.

There is a special pride that we can all take in knowing that leading edge research is being conducted right here in Winnipeg - and that, as much as Winnipeg is too often maligned for so many reasons, there are brilliant researchers who have chosen to come and stay here, as Lorne Brandes did, and who have achieved worldwide recognition for their achievements. Reading this book will give you an insight into just how remarkable – and difficult – it is to be at the cutting edge of scientific research, something that is being achieved in our very own city.

“Survival: A Medical Memoir” can be ordered online through www.FriesenPress.com/bookstore or Amazon.ca in hardcover or paperback, or downloaded in Kindle, iTunes, and Kobo formats. Although not on store shelves, it may also be ordered through McNally Robinson and Chapters/Indigo.

New book by Winnipeg oncologist Lorne Brandes tells fascinating tale

"Survival: A Medical Memoir", by Dr. Lorne Brandes

By BERNIE BELLAN

In his over 40-year career as a leading oncologist based in Winnipeg, Lorne Brandes developed a reputation not only as a caring doctor for thousands of patients, he was also a brilliant researcher and an acclaimed teacher at the University of Manitoba medical faculty. Now he has just published a memoir chronicling his years in cancer research during which he took a drug discovery from the laboratory into cancer patients.

In describing Dr. Brandes’s career, his publisher’s website states: “Over the years, he treated most types of cancer, but subsequently limited his practice to breast and prostate cancer. Until his retirement in September, 2015, he greatly enjoyed teaching the art and science of oncology to the many students and post-graduate physicians who rotated through his clinics.”

Now, after having retired from practice last fall, Dr. Brandes’ memoir is receiving wide acclaim, both for the scholarly manner in which he details the over 20-year portion of his career that was devoted to testing a drug known as DPPE, and for the human element he injects into telling that story.

I must admit that reading “Survival: A Medical Memoir” was not always easy for me, as there is quite a bit of science involved in the story of how the cancer-fighting antihistamine drug, DPPE, was first discovered and subsequently taken through the myriad of steps necessary to bring any new drug to market. In telling the story of how he first came to realize the potential benefits of DPPE, Dr. Brandes not only delves into the science behind the drug, he explores the very human side of the process of attempting to take it from the laboratory to the pharmacy.

The book was first brought to my attention by Abe Anhang, who suggested it as something we might want to review in The Jewish Post & News. Abe wrote: “Truth be told, this is a book that was written on two levels – one for the researchers and doctors who will read this book to confirm how difficult it is to shepherd a drug through the approval stages, and one for the layperson more interested in the human drama and the challenge that researchers face in the search for drugs that counter disease!

“The book emphasizes all the personal relationships one has to rely on; the dependence on the whims and judgement calls of government regulators who go by the book; and drug company executives who are primarily interested in bringing to market a product as quickly as possible, that can be sold at a profit. All are constantly on the lookout for the miracle drug, and with DPPE, it looked like they had one until the very late stage of the human clinical trials!

“This book is witness to a span of 20 years of effort! One has to marvel at the attention to detail Dr. Brandes had to recall, and then write it down in readable English! One might argue that its greatest strength (its detail) would appeal mostly to other researchers encountering similar problems. While too much detail may be seen as weakness by readers who are only interested in the drama, one can omit that detail and still understand the point that Dr. Brandes is making!

“As one reads this book the question that cries out for response is: if a professional researcher with an impeccable international reputation and training cannot make it happen, how does a drug ever make it through the process, and was this story just one of many, or was it illustrative of many? If one of many, how does ANY drug ever make it through to public distribution? Is it possible that a miracle cancer drug has already been discovered, but for some administrative reason (either at the research level, the government regulatory level or the drug company level) has faltered due to failure in the process, (in other words, human frailty at work)?”

In her Foreword to the book, Dr. Agnes Klein, Health Canada’s Director of the Centre for Evaluation of Radiopharmaceuticals and Biotherapeutics, and someone who was actively involved in approving DPPE for the first human trials, writes about Dr. Brandes: “To say that I saw him, from the start, as a ‘unique character’ is an understatement. He was passionate and persistent about his findings on DPPE, his basic and clinical research, as well as his practice of oncology. This passion likely came from his calling, but also from the Jewish dictum: ‘Tikun Olam’ (saving the world)…The story that he writes is a good read after all the years that have passed. It is a story that was worthwhile writing to have researchers understand that many endeavours do not end successfully. This is true, especially, in the realm of drug development…. I believe the book deserves to be published to remind researchers, physicians, other health care professionals and even a regulator like me, that the road to a successful drug is paved with pitfalls, despite all good intentions, and that while many active substances never ‘make it’, much new knowledge can be acquired along the way.”

What I think readers - even readers for whom the science in the book may be intimidating (count me among those individuals) – will find especially interesting is the fascinating description of how Dr. Brandes worked with a host of other brilliant researchers, many of whose names will no doubt be familiar to Winnipeggers. From Lyonel Israels to Brent Schacter to Frank LaBella – the list goes on and on – describing in full detail how scientific research is brought to fruition. In addition, there is a dizzying array of other characters who appear throughout the book, from other scientists to pharmaceutical company executives, drug regulators and even medical reporters.

Sadly, he also recounts the names of several individuals with whom he worked who have passed on. As a matter of fact, in reading this book, one can’t help but note the irony of how many other brilliant doctors and researchers who made their life’s work a search for better ways to combat cancer, themselves succumbed to this disease.

One other aspect that Jewish readers, especially, may find endearing in “Survivor: A Medical Memoir”, is Dr. Brandes’s self-deprecating wit and, I think it would be fair to say, his awareness of how much his being Jewish played a role in his career. In one chapter in particular, he describes how, prior to a very important meeting with drug company executives, he was warned to tone down his penchant for speaking his mind. His reply, that he would “think Yiddish but act British”, is as apt a description of the quandary that many Jews have faced, not only in academe, but in business as well.

The final takeaway that I’m sure anyone reading this book will be left with is an unmitigated admiration for scientific researchers who, while they may be recognized for their efforts by their peers, plumb away in laboratories for years, constantly worrying about applying for grants, about having papers accepted for publication, and of having their work undermined for no fair reason. While, to a certain extent, drug companies in this book come off looking as nothing more than avaricious opportunists willing to capitalize on years of research conducted in universities and funded by various levels of government – either directly or though government funded agencies such as CancerCare Manitoba – it is doctors and scientists such as Lorne Brandes and his colleagues who often provide the original research that paves the way for huge drug companies to bring miracle drugs to market. To have the patience to persist in the kind of agonizingly complex research that may come tantalizingly close to being translated into a “billion dollar drug”, as DPPE was once touted, yet ultimately to have that research come to naught – well, that requires a special kind of inner discipline.

There is a special pride that we can all take in knowing that leading edge research is being conducted right here in Winnipeg - and that, as much as Winnipeg is too often maligned for so many reasons, there are brilliant researchers who have chosen to come and stay here, as Lorne Brandes did, and who have achieved worldwide recognition for their achievements. Reading this book will give you an insight into just how remarkable – and difficult – it is to be at the cutting edge of scientific research, something that is being achieved in our very own city.

“Survival: A Medical Memoir” can be ordered online through www.FriesenPress.com/bookstore or Amazon.ca in hardcover or paperback, or downloaded in Kindle, iTunes, and Kobo formats. Although not on store shelves, it may also be ordered through McNally Robinson and Chapters/Indigo.