Since I started reposting my CTV.ca/health blogs, some of you have asked me to include written about Jack Layton. Here it is.

Did prostate cancer kill Jack Layton?

September 12, 2011 09:39 by Dr. Lorne Brandes

Few can forget their shock over Jack Layton’s gaunt appearance and raspy voice at the July 25th news conference where he stunned the country by announcing that, less than three months into the job, he was temporarily stepping down as Opposition leader “to fight a second type of cancer.” His previous prostate cancer “was no longer a threat,” he said.

Like all Canadians, I was very saddened. But, as an oncologist who treats prostate cancer, I was not surprised by this unhappy turn of events; as to the “different” cancer that Mr. Layton said he was now battling, I was doubtful. Let me tell you how I arrived at my conclusions and why I think the issue of his cancer is important to discuss from a medical and political perspective.

To begin, I remember being very concerned when he first made his diagnosis public in February, 2010. Only a week earlier, he had suffered pain from a “back injury” sustained while exercising. Now, painful back injuries can happen to anyone (fit like Jack, or not), but with a diagnosis of prostate cancer coming immediately on the heels of the back pain, I wondered whether there was a link. Did x-rays of his spine show something more concerning? If not caught early, prostate cancer can spread to the bones and cause pain.

Far from being reassured, my worry increased when Mr. Layton declared , “This year, more than 25,000 Canadian men are going to be diagnosed with treatable prostate cancer. And I've recently learned that I'm one of them.” He also told reporters that “he had already started a program of treatments for the cancer”, and that “so far the treatments are going well.”

But what exactly did he mean by “treatable”? Being the supreme optimist that he was, why did he not say “curable”? Both advanced and early prostate cancer are treatable, but only early prostate cancer is potentially curable. In the absence of further information, an air of uncertainty surrounded the type of “treatment” he was undergoing.

From an oncology perspective, the recommended treatment for a fit, healthy 60 year-old man with early prostate cancer is usually radical prostatectomy ; a second choice for localized disease is radical radiation therapy with curative intent. Yet, from his statement that he was “already on treatment”, it is clear that surgery had been discounted.

What about curative-intent radiotherapy? With the exception of pure brachytherapy treatment in carefully-selected (and often, older) patients, it is generally a complex treatment , in many instances preceded and/or followed by months of hormonal therapy, first to shrink the tumour and then prevent recurrence. Moreover, it usually takes a significant amount of time to carefully map out the radiation field, followed by five to six weeks of treatment and a period of recovery, often taking several weeks to a few months before a person is able to return to full activity.

But Jack’s return to Parliament Hill was only a matter of six weeks from the start of his “treatments”. Looking fit and, as always, upbeat, it was clear that he had come through them well. Yet, I could not shake the suspicion that, because the time interval was fairly short, they were palliative in nature, consisting of a week or 10 days of radiation to treat painful metastases in his spine (the “back injury”) and oral and/or injectable medications to block testosterone , the usual approach to treating Stage 4 (metastasized) prostate cancer.

Then, in March, 2011, 15 months after he was first diagnosed, came the revelation that he would require immediate surgery to repair a painful hip fracture. A hairline break, diagnosed a few weeks earlier, had suddenly gotten much worse on conservative management with pain killers and crutches.

After recovering from the operation, probing questions from reporters about the nature and treatment of the fracture, and whether his health problems would allow him to lead his team into the expected federal election were met with generalities and assurances that he would be up to the task.

When asked specifically whether he was still being treated for prostate cancer, Mr. Layton answered, “ Well, I work with my doctors on an ongoing basis like most people with cancer to monitor the situation. They’re happy with how things are going.” Any other details would remain a private matter between Jack and his doctors.

All the while, many in the oncology community, including me, suspected something more sinister was brewing. In the absence of trauma, benign hip fractures are extremely uncommon in a man his age. If it was not an “innocent” occurrence, two possibilities were bone thinning (osteoporosis) due to testosterone-blocking therapy or, even more ominously, a progressively-worsening fracture caused by prostate cancer cells destroying the bone. In that case, his disease was no longer responding to whatever treatment he had been receiving.

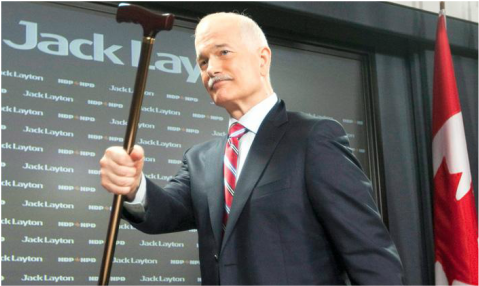

Whatever the cause, “the happy warrior” rallied after his hip surgery and, cane in hand, limped and then danced from strength to strength as he led the NDP to a remarkable showing in the general election, becoming Leader of Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition in the process.

But his victory was to be short-lived. Like Moses at the river Jordan, Jack Layton would not enter the promised land. A return of intense pain, accompanied by sweating, tiredness and weight loss were evident by early June.

Describing his “new battle with a second cancer” in his July news conference, Mr. Layton explained that his PSA test remained very low; therefore, the new problem was unrelated to his previous prostate cancer. His doctors appeared to concur, releasing a statement that “new tumours were discovered which appear to be unrelated to the original cancer.”

However, that opinion is subject to debate. Why? As cancer of any type progresses, the cells can change in appearance as their biological behaviour becomes more aggressive. And so it is with prostate cancer, where the tumour cells can become “dedifferentiated” (primitive in nature), metastasizing rapidly throughout the skeleton as well as to the liver, lungs and brain. Moreover, unlike the cells earlier in the disease, dedifferentiated prostate cancer cells may no longer produce PSA .

Therefore, an alternative explanation is that Mr. Layton’s “unrelated tumours” were really his old prostate cancer in a new form. A pathologist examining them under the microscope might not be able to state with certainty their exact nature or origin, as appeared to be the case here.

At the end of the day, from a medical and personal perspective, the identity of the new tumours mattered little. With such an aggressive cancer ravaging his body, and despite any attempts to slow down the process, Mr. Layton soon succumbed and all of Canada mourned his untimely passing.

Yet, questions persisted. When the nature of the “new cancer” that took her husband’s life came up in an interview, Olivia Chow demurred , telling the CBC’s Peter Mansbridge that no further information would be forthcoming so as not to “dash the hopes of other cancer patients suffering from the same illness.”

In the overall context of the information gap surrounding specific details of Jack Layton’s illness, Ms. Chow’s answer seems ingenuous at best, and evasive at worst.

If, as seems likely in my opinion, Mr. Layton, a candidate for Prime Minister of Canada, was diagnosed with incurable stage 4 prostate cancer prior to the general election, was his failure to come clean about the seriousness of his situation an abrogation of his responsibility to voters? Was Ms. Chow’s subsequent refusal to discuss the nature of the “second cancer” motivated by fear that admitting everything was related to advanced prostate cancer would hurt her late husband’s credibility and the future of the NDP?

If so, it appears she need not have worried. In response to an article in the Globe and Mail that asked whether Apple’s Steve Jobs and, likewise, Jack Layton, should have been more forthcoming about the details of their medical diagnoses, the vast majority of readers replied, “Ain’t nobody’s business.”

However, there were a few dissenters when it came to Mr. Layton:

“A politician with a serious illness should disclose the illness when running for office because people may vote differently if they know the facts….,” said one.

“Layton should have been clearer about the extent of his illness as he ran for re-election,” opined another.

“If he actually ran knowing he was in big trouble health wise, then perhaps…[a] debate…needs to occur as to whether this is proper or not,” commented a third.

I guess I’m in the minority, but given the facts as I see them, I agree with the dissenters, as well as with Globe and Mail writer, Andre Picard, that, like their American counterparts, Canadian politicians, especially those running for high office, owe the public full health disclosure.

After all, should we not subscribe to the premise that, in politics as in life, honesty is the best policy?

Did prostate cancer kill Jack Layton?

September 12, 2011 09:39 by Dr. Lorne Brandes

Few can forget their shock over Jack Layton’s gaunt appearance and raspy voice at the July 25th news conference where he stunned the country by announcing that, less than three months into the job, he was temporarily stepping down as Opposition leader “to fight a second type of cancer.” His previous prostate cancer “was no longer a threat,” he said.

Like all Canadians, I was very saddened. But, as an oncologist who treats prostate cancer, I was not surprised by this unhappy turn of events; as to the “different” cancer that Mr. Layton said he was now battling, I was doubtful. Let me tell you how I arrived at my conclusions and why I think the issue of his cancer is important to discuss from a medical and political perspective.

To begin, I remember being very concerned when he first made his diagnosis public in February, 2010. Only a week earlier, he had suffered pain from a “back injury” sustained while exercising. Now, painful back injuries can happen to anyone (fit like Jack, or not), but with a diagnosis of prostate cancer coming immediately on the heels of the back pain, I wondered whether there was a link. Did x-rays of his spine show something more concerning? If not caught early, prostate cancer can spread to the bones and cause pain.

Far from being reassured, my worry increased when Mr. Layton declared , “This year, more than 25,000 Canadian men are going to be diagnosed with treatable prostate cancer. And I've recently learned that I'm one of them.” He also told reporters that “he had already started a program of treatments for the cancer”, and that “so far the treatments are going well.”

But what exactly did he mean by “treatable”? Being the supreme optimist that he was, why did he not say “curable”? Both advanced and early prostate cancer are treatable, but only early prostate cancer is potentially curable. In the absence of further information, an air of uncertainty surrounded the type of “treatment” he was undergoing.

From an oncology perspective, the recommended treatment for a fit, healthy 60 year-old man with early prostate cancer is usually radical prostatectomy ; a second choice for localized disease is radical radiation therapy with curative intent. Yet, from his statement that he was “already on treatment”, it is clear that surgery had been discounted.

What about curative-intent radiotherapy? With the exception of pure brachytherapy treatment in carefully-selected (and often, older) patients, it is generally a complex treatment , in many instances preceded and/or followed by months of hormonal therapy, first to shrink the tumour and then prevent recurrence. Moreover, it usually takes a significant amount of time to carefully map out the radiation field, followed by five to six weeks of treatment and a period of recovery, often taking several weeks to a few months before a person is able to return to full activity.

But Jack’s return to Parliament Hill was only a matter of six weeks from the start of his “treatments”. Looking fit and, as always, upbeat, it was clear that he had come through them well. Yet, I could not shake the suspicion that, because the time interval was fairly short, they were palliative in nature, consisting of a week or 10 days of radiation to treat painful metastases in his spine (the “back injury”) and oral and/or injectable medications to block testosterone , the usual approach to treating Stage 4 (metastasized) prostate cancer.

Then, in March, 2011, 15 months after he was first diagnosed, came the revelation that he would require immediate surgery to repair a painful hip fracture. A hairline break, diagnosed a few weeks earlier, had suddenly gotten much worse on conservative management with pain killers and crutches.

After recovering from the operation, probing questions from reporters about the nature and treatment of the fracture, and whether his health problems would allow him to lead his team into the expected federal election were met with generalities and assurances that he would be up to the task.

When asked specifically whether he was still being treated for prostate cancer, Mr. Layton answered, “ Well, I work with my doctors on an ongoing basis like most people with cancer to monitor the situation. They’re happy with how things are going.” Any other details would remain a private matter between Jack and his doctors.

All the while, many in the oncology community, including me, suspected something more sinister was brewing. In the absence of trauma, benign hip fractures are extremely uncommon in a man his age. If it was not an “innocent” occurrence, two possibilities were bone thinning (osteoporosis) due to testosterone-blocking therapy or, even more ominously, a progressively-worsening fracture caused by prostate cancer cells destroying the bone. In that case, his disease was no longer responding to whatever treatment he had been receiving.

Whatever the cause, “the happy warrior” rallied after his hip surgery and, cane in hand, limped and then danced from strength to strength as he led the NDP to a remarkable showing in the general election, becoming Leader of Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition in the process.

But his victory was to be short-lived. Like Moses at the river Jordan, Jack Layton would not enter the promised land. A return of intense pain, accompanied by sweating, tiredness and weight loss were evident by early June.

Describing his “new battle with a second cancer” in his July news conference, Mr. Layton explained that his PSA test remained very low; therefore, the new problem was unrelated to his previous prostate cancer. His doctors appeared to concur, releasing a statement that “new tumours were discovered which appear to be unrelated to the original cancer.”

However, that opinion is subject to debate. Why? As cancer of any type progresses, the cells can change in appearance as their biological behaviour becomes more aggressive. And so it is with prostate cancer, where the tumour cells can become “dedifferentiated” (primitive in nature), metastasizing rapidly throughout the skeleton as well as to the liver, lungs and brain. Moreover, unlike the cells earlier in the disease, dedifferentiated prostate cancer cells may no longer produce PSA .

Therefore, an alternative explanation is that Mr. Layton’s “unrelated tumours” were really his old prostate cancer in a new form. A pathologist examining them under the microscope might not be able to state with certainty their exact nature or origin, as appeared to be the case here.

At the end of the day, from a medical and personal perspective, the identity of the new tumours mattered little. With such an aggressive cancer ravaging his body, and despite any attempts to slow down the process, Mr. Layton soon succumbed and all of Canada mourned his untimely passing.

Yet, questions persisted. When the nature of the “new cancer” that took her husband’s life came up in an interview, Olivia Chow demurred , telling the CBC’s Peter Mansbridge that no further information would be forthcoming so as not to “dash the hopes of other cancer patients suffering from the same illness.”

In the overall context of the information gap surrounding specific details of Jack Layton’s illness, Ms. Chow’s answer seems ingenuous at best, and evasive at worst.

If, as seems likely in my opinion, Mr. Layton, a candidate for Prime Minister of Canada, was diagnosed with incurable stage 4 prostate cancer prior to the general election, was his failure to come clean about the seriousness of his situation an abrogation of his responsibility to voters? Was Ms. Chow’s subsequent refusal to discuss the nature of the “second cancer” motivated by fear that admitting everything was related to advanced prostate cancer would hurt her late husband’s credibility and the future of the NDP?

If so, it appears she need not have worried. In response to an article in the Globe and Mail that asked whether Apple’s Steve Jobs and, likewise, Jack Layton, should have been more forthcoming about the details of their medical diagnoses, the vast majority of readers replied, “Ain’t nobody’s business.”

However, there were a few dissenters when it came to Mr. Layton:

“A politician with a serious illness should disclose the illness when running for office because people may vote differently if they know the facts….,” said one.

“Layton should have been clearer about the extent of his illness as he ran for re-election,” opined another.

“If he actually ran knowing he was in big trouble health wise, then perhaps…[a] debate…needs to occur as to whether this is proper or not,” commented a third.

I guess I’m in the minority, but given the facts as I see them, I agree with the dissenters, as well as with Globe and Mail writer, Andre Picard, that, like their American counterparts, Canadian politicians, especially those running for high office, owe the public full health disclosure.

After all, should we not subscribe to the premise that, in politics as in life, honesty is the best policy?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed