An important study just published in the Annals of Internal Medicine has found no evidence that receiving a blood transfusion from donors with a neurodegenerative disease, such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's, increases the risk for neurodegenerative disease in the recipient. This finding may go some distance in allaying concerns that these diseases can be spread from person to person. Underlying this worry has been scientific evidence that abnormal (misfolded) proteins, similar to prions, are the likely cause of many neurodegenerative disorders that spread through the central nervous system over time.

That said, did you know that prion-like proteins, implicated in dementia, also appear to be vital for the formation and retention of normal memory? Read more in this re-posted CTV.ca/health blog I wrote in 2012.

That said, did you know that prion-like proteins, implicated in dementia, also appear to be vital for the formation and retention of normal memory? Read more in this re-posted CTV.ca/health blog I wrote in 2012.

The narrow line between forming memories and losing them

by Dr. Lorne Brandes Jul. 11, 2012

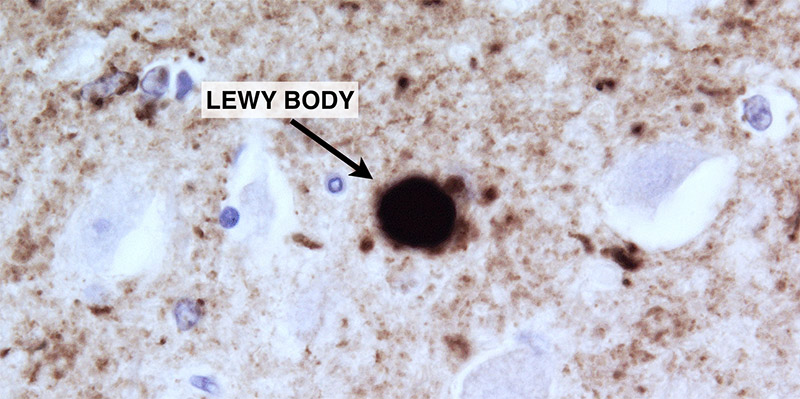

Judging by the number of “recommenders” on the Facebook link, a lot of readers were interested in last week’s blog, Targeting iron in Parkinson’s Disease (PD). Apart from the role that iron may play in neurodegenerative diseases, perhaps what fascinated most people is the likelihood that a prion-like protein, called alpha-synuclein , may initiate Parkinson’s and then spread it from one brain area to another.

To review, prions (derived from “protein infection”) can exist in two forms, each exhibiting a distinct shape and behavior:

- in their normal (or “recessive”) form, prions have a corkscrew shape, called an alpha-helix; recessive prions are manufactured by our genes, are the most common type, and reside harmlessly in cells.

- however, when, for a variety of reasons, several recessive prions cluster together to form oligomers [from the Greek “oligo”, meaning “a few”], their shape changes into a misfolded (“dominant”) protein that resembles a pleated sheet.

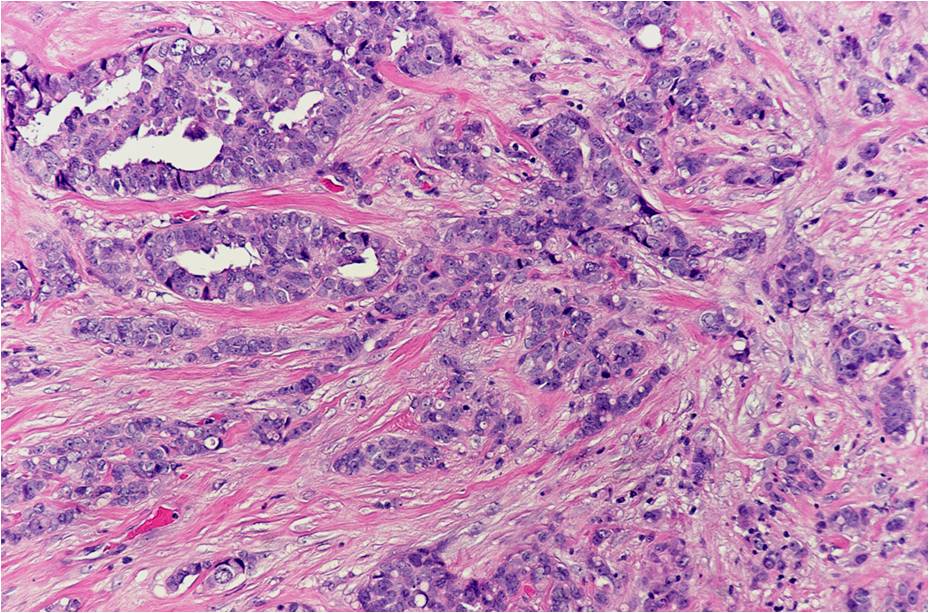

Now, with the identification of neurotoxic prion-like proteins, such as alpha-synuclein in PD, and beta-amyloid and tau in Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), scientists are openly discussing the hypothesis that many common human neurodegenerative diseases are “ prion disorders ”, not unlike mad cow disease (BSE) in cattle and scrapie in sheep.

But trumping even that possibility is the amazing discovery that those very same dominant prion oligomers are essential for the formation of long-term memory!

The earliest indication that this might be so surfaced over a decade ago in the Columbia University laboratory of Dr. Eric Kandel, who shared the 2000 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his pioneering work in brain signaling (more specifically, how the brain responds to environmental stimuli and, in the process, forms and retains memories).

While experimenting on the sea slug (Aplysia), a model of nerve function developed by Kandel, Dr. Kausic Si, a postdoctoral fellow, discovered that a vital protein, called CPEB , continuously replenished other proteins that maintain and enhance the function of new nerve endings, or synapses , that sprout in response to operant conditioning (learning), or to repeated exposure to serotonin , a brain neurotransmitter.

That of itself was an important new discovery. Yet, both Si and Kandel knew that the life of most proteins is short, usually hours. How was CPEB, itself a protein, able to persist and sustain the new nerve endings for long periods of time, perhaps for the life of the sea slug?

After analyzing its structure, Si came up with a startling finding. Kandel describes what happened next in his must-read book, “ In Search of Memory ”:

“I remember it was a beautiful New York afternoon in the spring of 2001, the bright sunlight rippling off the Hudson River outside my office windows, when Kausik walked into my office and asked, ‘What would you say if I told you that CPEB has prion-like properties?’

“A wild idea! But if true, it could explain how long-term memory is maintained in synapses… Clearly, a self-perpetuating molecule could remain at a synapse indefinitely, regulating the local protein synthesis needed to maintain newly grown synaptic terminals.”

Further experiments conducted in yeast cells by Si cemented the observation; CPEB, did indeed have dominant prion-like properties.

But it was one thing to show that CPEB resembled a dominant prion and another to establish conclusively that this likeness was essential to forming and maintaining long-term memory.

That proof came earlier this year. In a study published in Cell, scientists led by Dr. Si, now at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, showed that, like CPEB in the sea slug, Orb2, a similar nerve cell protein in fruit flies, looks and behaves like a dominant prion oligomer.

Once that was confirmed, Si and his colleagues carried out two operant conditioning experiments in male fruit flies: learning to avoid a female mated to another male; and learning to associate a specific odour with a food (sugar) reward. The result? Orb2 conferred long-term avoidance and association memory (lasting beyond 48 hours) in normal fruit flies. In contrast, mutant fruit flies that carried only a recessive (non-replicating) form of Orb2, retained what they had learned for 24 hours and then completely forgot when retested at 48 hours.

"Self-sustaining populations of [dominant prion oligomers] located at synapses may be the key to the long-term….changes that underlie memory; in fact, our finding hints that oligomers play a wider role in the brain than has been thought," Dr. Si told Science Daily.

He and his team now plan to see how long Orb2 must be present to keep a memory alive. "We suspect that [it] need[s] to be continuously present, because [it is] self-sustaining in a way that [recessive] Orb2 [in mutant fruit flies] is not," Si commented .

As Dr. Kandel notes in his book : “…basic science can be like a good mystery novel with surprising twists: some new, astonishing process lurks in an undiscovered corner of life and is later found to have wide significance. This particular finding [that CPEB is prion-like] was unusual in that the molecular processes underlying a group of strange brain diseases are now seen also to underlie long-term memory, a fundamental aspect of healthy brain function. Usually, basic biology contributes to our understanding of disease states, not vice versa.”

By now, it should be apparent that there is a fine line between forming and losing memory: in normal circumstances, dominant prions giveth; in pathological circumstances, they taketh away.

An answer to the riddle of what goes awry to make them “taketh away” could allow us to prevent many, if not all, neurodegenerative diseases.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed